CONTEXT

Start of the War and Occupation

With the attack of the German Wehrmacht on Poland in September 1939, the Second World War began. On October 28, 1940, Italy—Nazi Germany’s ally—attacked Greece. By the end of April 1940, Italy, Germany, and allied Bulgaria had conquered the Greek mainland. In 1941, they divided Greece into occupied zones. The German-occupied parts were under a military administration that worked with a Greek collaboration government.

Occupied Zones

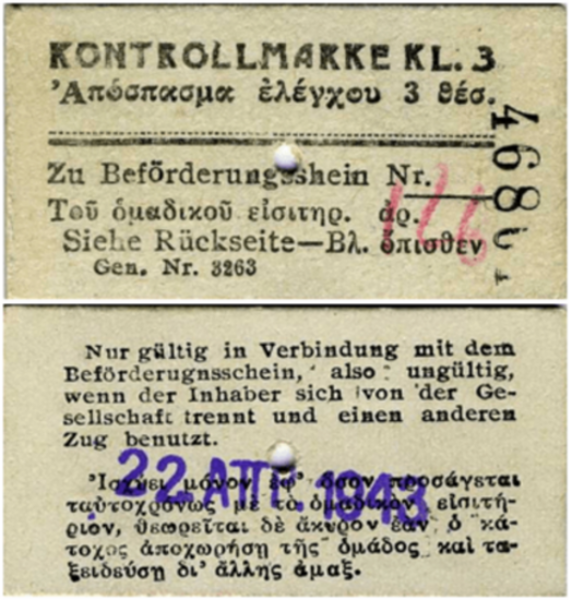

In dividing Greece, Germany ceded large sections to the Italian and Bulgarian occupiers, but kept areas that were important for the war effort. Karya is situated on the rain line Thessaloniki–Athens, which moved in large part through the Italian-occupied zone. However, the Germans took control of the entire railway network and significant ports. Their goal was to be able to transport natural resources and commodities crucial to the war effort as smoothly as possible to Germany.

Occupational Terror and Resistance

The German occupation in Greece was particularly brutal: the Wehrmacht ruthlessly plundered the country. The economy collapsed, and hundreds of thousands of Greeks died from the consequences of famine. Resistance formed against the occupation. The two largest groups were the communist ELAS and the national-republican EDES. From the fall of 1942, the partisans controlled large areas in the mountains in central Greece. The occupiers responded harshly to the resistance fighters; they took civilians hostage and shot them to death. Hundreds of villages were burned to the ground as a repression measure.

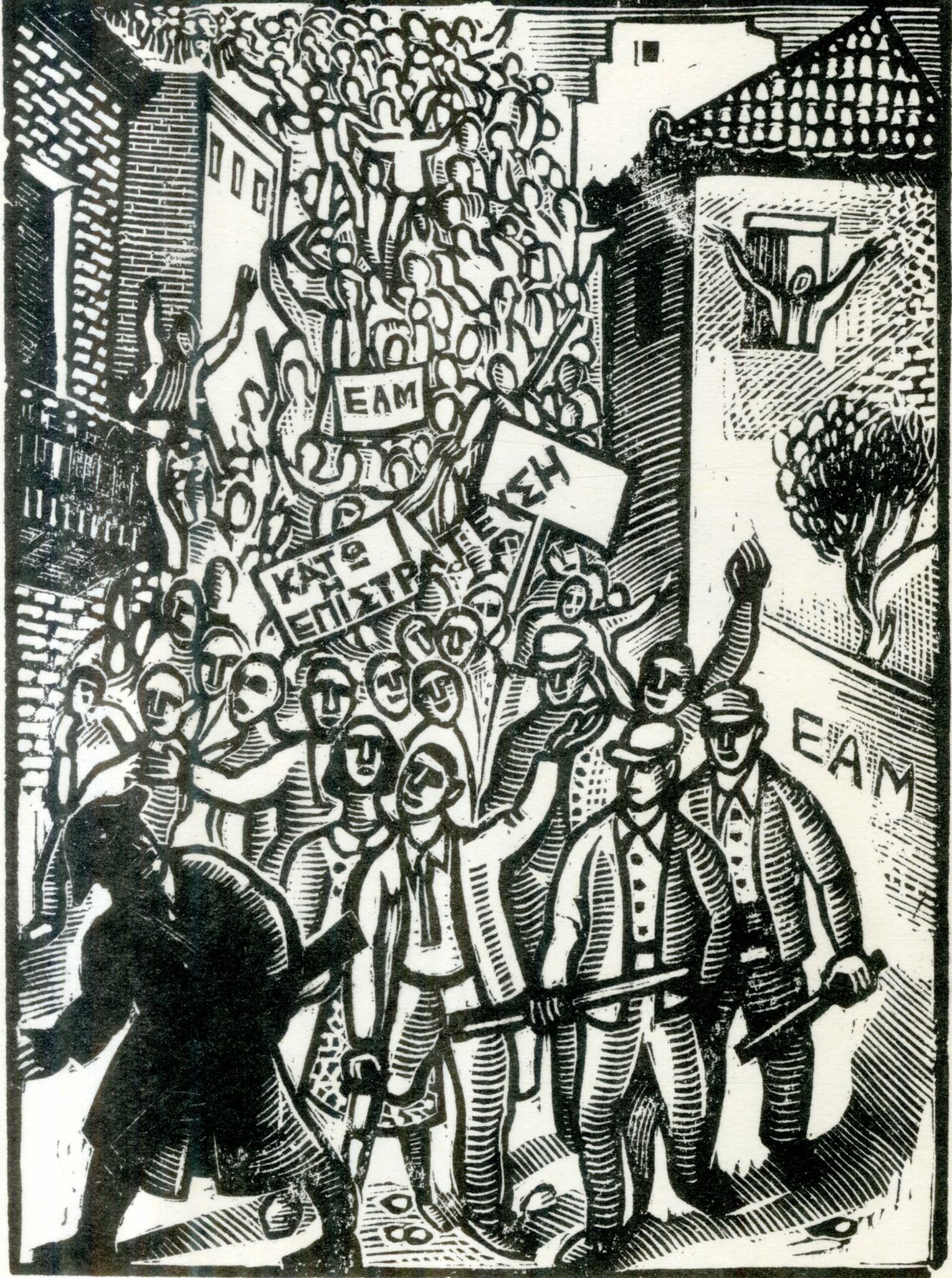

Forced Labour and Protest

More than 100,000 non-Jewish and Jewish Greeks were forced to perform labour. On January 30, 1943, the Germans introduced a work obligation for men between 18 and 50 years old in all of the occupied zones of Greece. Following calls by resistance groups, in February and April 1943 thousands protested in the big cities against this obligation. The ordinance was rescinded, but the Germans began conducting raids, arresting tens of thousands and bringing them to detention camps, from where they were sent to forced labour, or to concentration camps in Nazi Germany.

Jewish Life in Thessaloniki

The city of Thessaloniki was an important religious and cultural centre of European Judaism. Until 1912, it was part of the Ottoman Empire. Around 1900, half of Thessaloniki’s population was Jewish. Most of the Jews there were Sephardic: their ancestors were driven from Spain and Portugal around 1500. For generations, they preserved their language, Judäo-Spanish (Ladino), and their customs. After waves of emigration, in 1940 approximately 50,000 Jews were still living in Thessaloniki. Immediately following the division of Greece, starting in May 1941, the Germans began to persecute the Jewish populace.

Persecution of Jews in Thessaloniki

The Jewish populace of Thessaloniki was the first to be persecuted by the Germans. The Germans shut down Jewish newspapers, plundered artworks owned by the Jewish community, and fomented hate against Jews amongst Christian Greeks by claiming that the Jews were responsible for the famine. At the end of 1942, the centuries-old Jewish cemetery was completely torn down.

“Black Saturday”

The Wehrmacht in Thessaloniki wanted to use Jewish men for forced labour, so they assembled more than 9,000 of them, aged 18 to 45, on a Saturday (the Jewish Sabbath), July 11, 1942, at the centrally located Eleftherias Square. There they were forced to stand for hours in the sun; they were ridiculed, and German soldiers and collaborators beat them. A few weeks later, 3,500 of them were sent to forced labour at various locations in northern Greece.

Ghetto and Forced Evictions

The Germans imposed a curfew for Jews and forced them to wear yellow stars. In 1943 they established ghetto districts. The residential district “Baron Hirsch,” near the train station, was turned into a transit camp. In March 1943, transports from here to the German extermination camp Auschwitz began. At the same time, at least 1,500 men were sent to forced labour, including to the station at Karya.

The Deportations

In 19 transports, between March 15 and August 1943, nearly 46,000 Jewish children, women, and men were deported from Thessaloniki to Auschwitz. The trip lasted at least five days. Immediately upon their arrival, the SS murdered most of them in gas chambers. More died as the result of forced labour, violence, illness, and/or malnutrition. In 1944, transports from the rest of Greece followed. In total, almost 60,000 Jews were deported to the extermination camp and murdered.

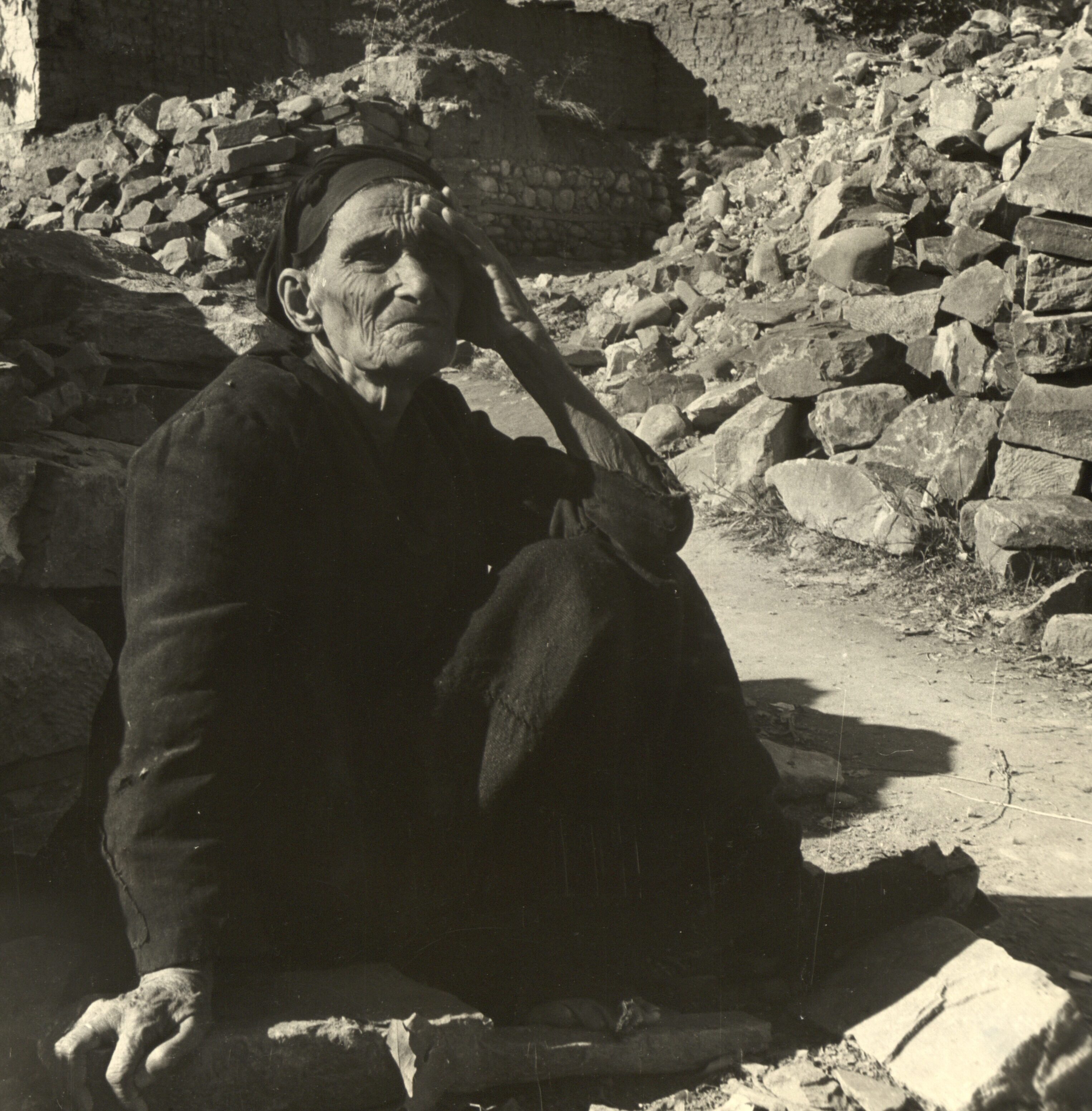

The End of the German Occupation

In October 1944, the Wehrmacht pulled out of Greece. As a consequence of their deliberate destruction of houses, villages, and transport routes as well as their theft of Greek natural resources and commodities, the country’s economy was left in a disastrous state. Tens of thousands of Greeks were suffering from malnutrition and infectious diseases. In addition, in December 1944 new conflicts arose: the Greek government returned from exile and was supported by the British in its quest to defeat the partisan army ELAS.

Jewish Life after 1945

Only around 10,000 Greek Jews survived the Holocaust. Most of the survivors suffered from the traumatic experience of persecution for the rest of their lives. The reconstruction of synagogues, businesses, and homes was often possible only with international aid, such as from the American Joint Distribution Committee. By the start of the 1950s, due to material hardship but also the prevailing anti-Jewish mood, approximately 5,000 of the survivors had emigrated to Palestine (from 1948, Israel) or the United States.

The Civil War 1946–1949

In 1946 the Greek monarchy was reconstituted. In the same year the communist Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) started a guerilla war against it. Jewish men also had to fight against the DSE guerillas in the Greek army. The war ended in 1949 with the defeat of the leftists. Communists were subsequently persecuted—including Jews who had survived with the help of communist resistance groups. More than 50,000 Greeks lost their lives in the civil war. At the start of the 1950s, Greece deported the last of these Jewish political prisoners to Israel.